The great, genre-defying trumpeter Miles Davis once joked about the pianist’s off-key phrasing on one of his seminal numbers, “Monk plays the wrong changes to ‘Round Midnight.’ ”

“Two more sides by the pianist who did NOT invent bop, and generally plays bad, though interesting, piano,” dismissed a 1949 DownBeat review of Monk’s “Misterioso” and “Humph.” Still, among his peers, Monk was respected as an original.

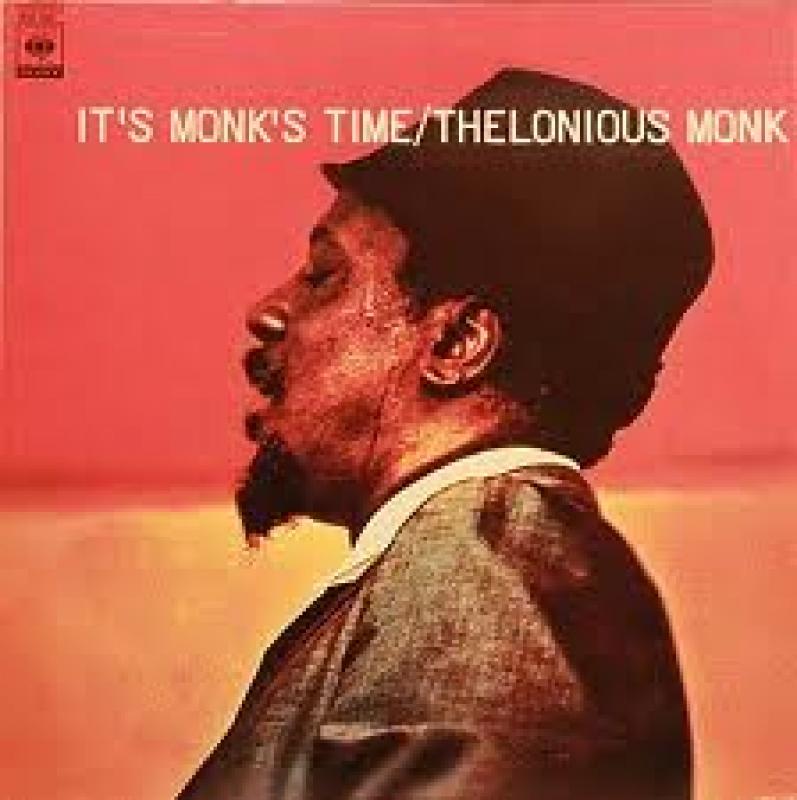

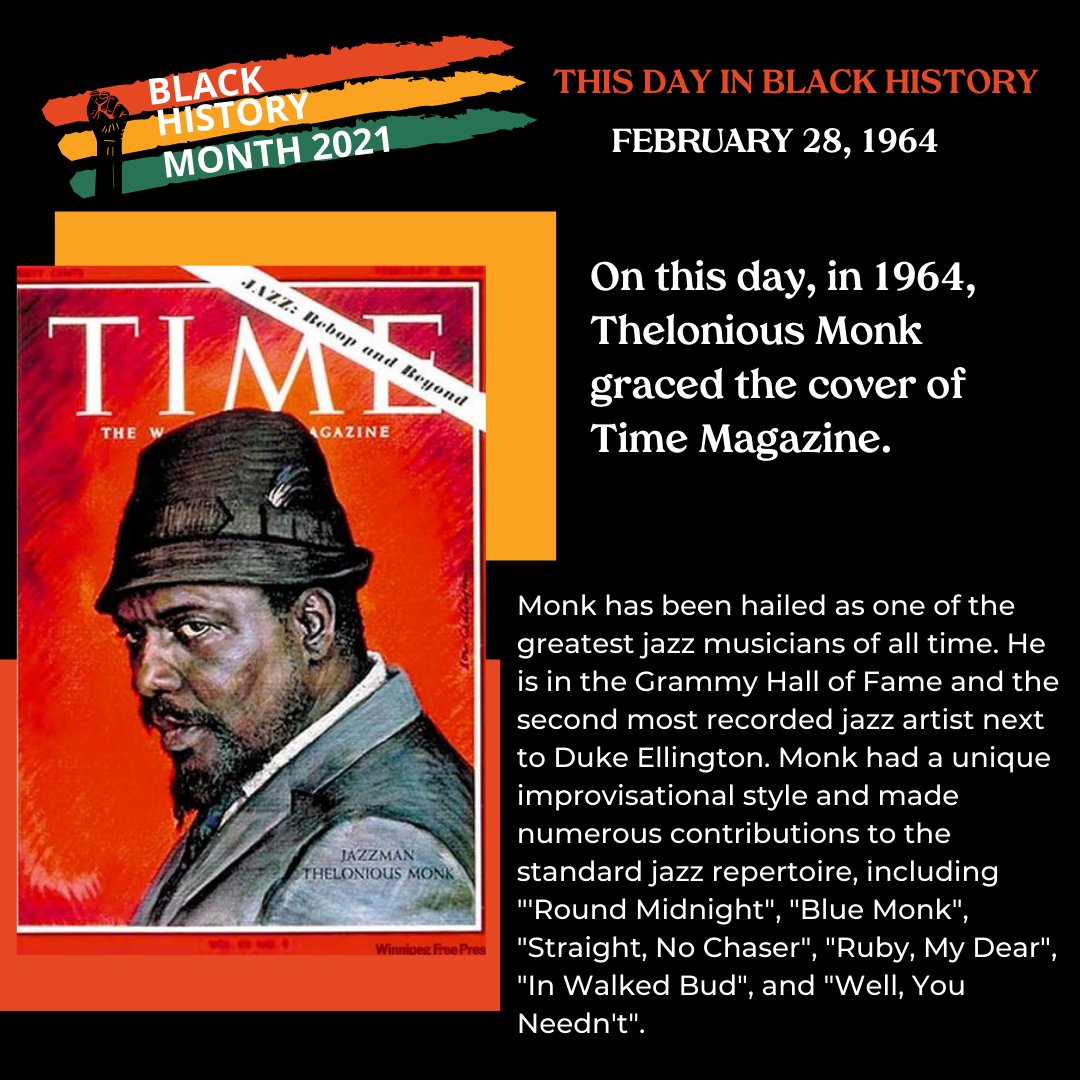

With his subterranean hipster image (pointy goatee, dark shades and assorted headgear that included his trademark Chinese skullcap) and compositions brimming with improvised dissonance and playful melodicism, Monk was at times seen through a polarizing lens. Indeed, before his 1957 breakthrough at the New York jazz club Five Spot, the bebop innovator was pegged, at best, as an entertaining oddity and, at worst, as a harebrained punch line lacking taste and technique. Thelonious Monk on a New York winter’s day. But Monk’s ascent to timeless jazz great had been turbulent. Ain’t that a bitch?” he once mused in typical quirky Monk-ism fashion. Monk was oblivious to the cultural and racial tug-of-war. Music writer LeRoi Jones, who went on to become outspoken literary figure Amiri Baraka, found it strange that the good folks at Time had the audacity to believe that they had somehow discovered Monk’s greatness.Ĭelebrated jazz critic Leonard Feather, in a response published in DownBeat magazine, balked at Farrell’s nods to Monk’s alleged drug use - “Every day is a brand-new pharmaceutical event for Monk: alcohol, Dexedrine, sleeping potions, whatever is at hand, charge through his bloodstream in baffling combinations …” - as further trafficking in stereotypes denigrating a race of people who have “suffered not decades but centuries of damage.” Other critics who also championed Monk weren’t buying it. Headgear, check keyboards, check - Thelonious Monk goes to work. Farrell praised Monk for getting the “serious recognition he deserved all along.” He had signed a three-album deal in 1962 with Columbia Records and was cashing in on sold-out tours in Europe with his white-hot quartet - Charlie Rouse on tenor sax, John Ore on bass and Frankie Dunlop on drums. Farrell showered emphatic reverence for the in-demand genius, who after years of money woes was making a more than decent living. That delay gave more time for writers to debate the improbable cover story titled “The Loneliest Monk” before it was unveiled to the public. 28, 1964, that the magazine published the issue showcasing Monk. Time shredded its Monk copies and, on that somber Friday, ran an issue with the new president, Lyndon B. Farrell conducted his interviews, photographer Boris Chaliapin shot a portrait of a natty Monk and the issue headed off to the printing plant. Despite Colomby’s trepidation, the Monk cover was scheduled for the issue that would hit newsstands Friday, Nov.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)